When Perfect Code Isn't Enough: Test-Driven Business Modelling for Product Success

Discover how TDD principles applied at business level can prevent expensive failures and accelerate learning.

TWIL episode #15 - August 2025

Ten years ago, I worked on what was technically one of the most challenging, yet best-executed projects of my career: a highly secure data exchange and collaboration platform for health professionals.

The technical execution got a lot of love: the security was top-notch (and frankly, quite innovative), every component was thoroughly tested, and the architecture could handle large loads. We were ready for a massive influx of users and data!

Yet the reality was starkly different: the actual usage of the platform stayed way below expectations.

Fast forward 15 years and many lessons learned, I better understand why... We'd put all our attention to delivering top quality (yes, we did it right), but did not sufficiently test the underlying business assumptions (was it the right thing at the right moment?).

In this newsletter, I'll show you how to avoid this pitfall. I'll apply the ideas of test-driven development (TDD) beyond code to come up with better business strategies and product decisions, cheaper, quicker, and less risky. So you can use this approach yourself to identify the critical business assumptions for your project or product, design minimal experiments to validate them, and structure your roadmap around learning rather than features.

Understanding Test-Driven Development for Business Context

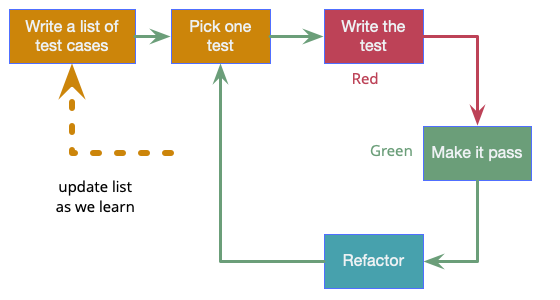

Before we dive into business decisions, let's clarify what makes Test-Driven Development so powerful. TDD follows a simple cycle: Red-Green-Refactor. First, you write a failing test (red), which you pick from the list of tests you imagined. Next, you implement just enough code to make it pass (green), to conclude with cleaning up your implementation if needed (refactor).

The list of tests provides you with context (clarity) and can be adapted at any time with the learnings from the red-green-refactor cycle. From that context, you pick one test (focus).

Writing the test first forces you to think about what you want to achieve and makes your expected result crystal clear. Next, you only do the minimal implementation in that middle step. You don't build elaborate solutions—you write the smallest amount of code that satisfies the test. This constraint forces you to think clearly about requirements and prevents over-engineering.

TDD also provides continuous feedback. Each test tells you immediately whether your assumptions about the system are correct. If a test fails, you know something's wrong before you've invested too much effort in the wrong direction. And whether a test passes or fails, it can help you expand the list of tests, which means you are building a better understanding of your context.

These same principles—minimal implementation, continuous validation, and rapid feedback—are exactly what business strategy needs.

The Three Pillars of Business Testing

In business, your "tests" are assumptions about three critical areas:

Desirability assumptions focus on customer needs and wants. Will people actually use what you're building? Do they have the problem you think they have? Are they willing to change their behaviour to adopt your solution?

Feasibility assumptions examine your ability to deliver. Can you(r team) build this with the current resources? Do you have the necessary skills and technology? Are there regulatory or technical constraints you haven't considered?

Viability assumptions question the business fundamentals. Can you make money from this? Will the unit economics work at scale? Do you have a sustainable competitive advantage?

Most failed projects stumble because teams never properly test one of these three pillars. They assume customers want their solution (untested desirability), that they can build it efficiently (untested feasibility), or that it'll be profitable (untested viability).

Implementing the Business TDD Cycle

So how do you avoid missing assumptions or investing too much in the wrong direction?

The 1st step is listing the assumptions underlying your project or business model. Be ruthlessly honest—if you're assuming something without evidence, write it down. A typical product initiative might have dozens of assumptions across all three pillars. And this list will grow as you learn more!

Next, identify your riskiest assumption(s). These are the ones that, if wrong, would fundamentally undermine your project. Ask yourself: "If this assumption is false, does everything else fall apart?" Those are your critical tests to run first.

Now comes the crucial step: design minimal experiments to validate each critical assumption. Just like in code TDD, you want the smallest possible implementation that gives you maximal feedback.

I deliberately use the word maximal. Business choices differ fundamentally from code: in development, a test is either green or red—it passes or fails. Business validation isn't binary. You don't get a simple pass/fail result from your experiments.

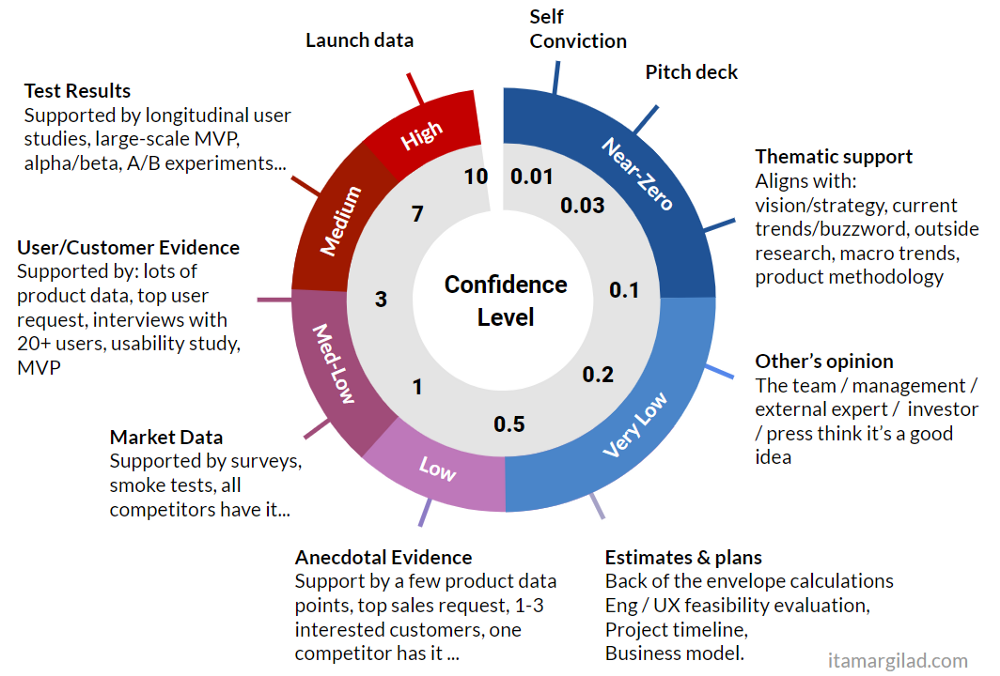

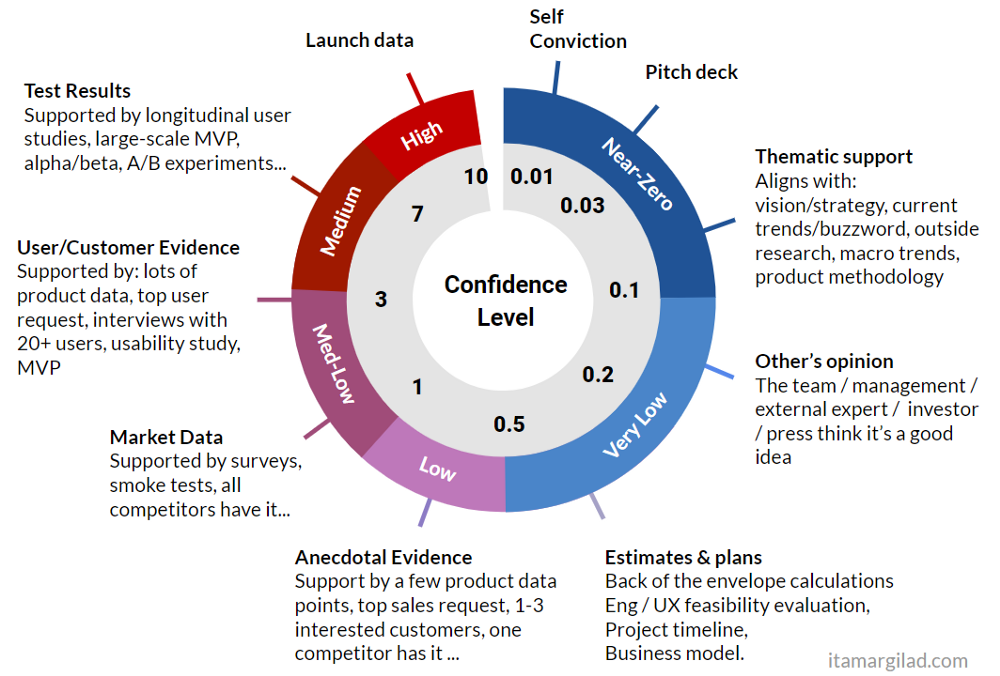

Instead, you build confidence levels in your assumptions. Each type of evidence provides different confidence levels—from self-conviction and opinions (near-zero confidence) to anecdotal customer feedback (low confidence) to market research and user studies (medium confidence) to actual usage data from real implementations (high confidence).

This confidence-based approach changes how you think about validation. Rather than looking for definitive proof, you're building evidence that increases your confidence in proceeding. A customer survey might give you medium-low confidence, but actual usage data from an MVP gives you high confidence.

For desirability, this might mean creating a landing page or organising discovery calls with potential users to gauge interest before building any product. For feasibility, you might prototype the most technically challenging component first. For viability, you could test pricing with a small customer segment.

The key is making these experiments as small and fast as possible while generating reliable data that increases your confidence level. You're not looking for that binary "green light," but rather building sufficient confidence to justify the next level of investment.

Structuring Your Roadmap Around Learning

Test-driven business modelling gets really powerful when you start to organise your work around it. Instead of organising your roadmap around features or deliverables, structure it around assumptions you need to validate and use that as a way to rally your entire team around this learning trajectory.

Each roadmap theme becomes a major assumption cluster. Your sprints and initiatives focus on running experiments to test these assumptions. Success is no longer measured by features shipped, but by assumptions validated or invalidated.

This approach will save you (a lot!) of money and time. When early experiments show your core assumptions are wrong, you can pivot quickly. Saving you from investing massive amounts in work that leads nowhere...

You will also think differently about failure. In traditional roadmapping, a feature that doesn't get adopted feels like wasted effort. In assumption-driven roadmapping, learning that customers don't want something is valuable—it's a test that helped you avoid building the wrong thing at scale.

Playbook for Better Results

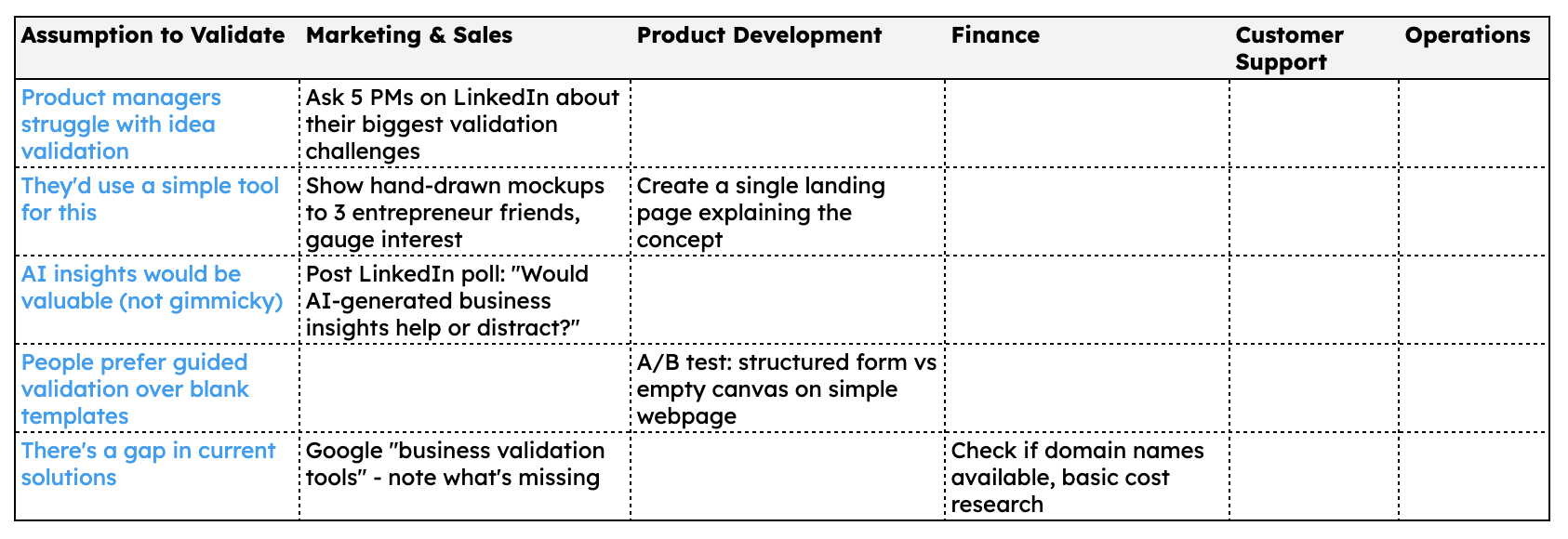

I'm just starting to explore a little software tool idea for product managers and entrepreneurs who want optimal insight into their ventures and get the best possible start. Rather than building first and validating later, here's a sneak preview of how I plan to test critical assumptions with minimal investment in the early stages.

Notice the intentionally sparse table—a lot of cells are empty because I'm in exploration mode, not execution mode. Each filled cell represents an experiment I can run without building anything substantial. The goal isn't comprehensive validation; it's gathering just enough evidence to decide whether this idea deserves more serious investigation and another dose of my time.

This is test-driven business modelling at its most lightweight: validate before you invest.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

As usual, there are several attention points:

- The biggest pitfall is when you become attached to an idea too early. The statement "If I/we work hard/invest/... enough, it will become a success ..." has been a costly statement for many, both financially and personally.

- Another big challenge is to keep experiments minimal. Remember: you want the smallest possible experiment that provides maximal feedback. So once you have designed an experiment, challenge yourself: What if there is only 1/2 of the budget or time?

- To make quick progress, keep your work in progress low: avoid testing too many assumptions in parallel. It will spread your efforts, obfuscate the learnings and will simply cost you money (that may not be worth it - yet).

- A trap is confirmation bias. Teams design experiments hoping to prove their assumptions right rather than genuinely testing them. This is linked to emotional attachment to an idea, so be wary! The strongest experiments are those that could easily disprove your hypothesis.

- Finally, don't ignore negative results. A failing test in code tells you something's wrong—same with business assumptions. Pivot quickly when experiments show your assumptions are incorrect.

The Competitive Advantage of Business TDD

Companies practising test-driven business modelling waste fewer resources and find the right direction faster. They fail quickly and cheaply on bad ideas while doubling down on validated concepts. In an era where business models change rapidly, this learning velocity becomes a sustainable competitive advantage.

Moreover, this approach builds organisational capability. Teams become comfortable with uncertainty and skilled at designing experiments. They develop intuition for which assumptions are most critical and how to test them efficiently.

The discipline of constant assumption testing also keeps teams honest about what they actually know versus what they hope is true. This intellectual honesty leads to better strategic decisions and more resilient business models.

What's the most critical assumption underlying your current project, and how might you design a minimal experiment to test it?

I wish you a lot of fun thinking about the things that need to be true for your work to have an impact! And a lot of fun running experiments 💪

Further Reading and References